Mergers and Acquisitions Case Studies and Interviews

A Guide for Future Lawyers

Enjoyed this post? Check out our new Mergers and Acquisitions Course, which covers exactly what you need to know about M&A for interviews at top commercial law firms. Free access to this course is given to all premium subscribers.

If you don’t know what commercial law is or what commercial lawyers do, it’s hard to know whether you want to be one.

I’m going to discuss one aspect of commercial law: mergers and acquisitions or “M&A”, and with any luck, convince you it can be exciting.

I’ll also cover many of the aspects of mergers and acquisitions that you need to know for law firm interviews and case study exercises.

Let’s begin with an example, which highlights the impact of mergers and acquisitions. In 2017, Amazon bought Whole Foods and became the fifth largest grocer in the US by market share. This single manoeuvre shed almost $40 billion in market value from companies in the US and Europe.

The fall in value of rival supermarkets reflected fears over Amazon’s financial capacity and its potential to win a price war between supermarkets. Amazon the customer data to understand where, when and why people buy groceries, and it has the technology to integrate its offline and online platforms. When you’re in the race to be the first trillion-dollar company, acquisitions can take you a long way (Edit: In August 2018, Apple managed to beat Amazon to win this title).

But not all companies share Amazon’s success. In fact, out of 2,500 M&A deals analysed by the Harvard Business Review, 60% destroyed shareholder value.

That begs the question:

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

Why do firms merge or acquire in the first place?

I’ll use law firms as an example. You’ll have seen that they often merge, or adopt structures called Swiss vereins, which allow law firms to share branding and marketing but keep their finances and legal liabilities separate.

In the legal world, it can be hard to find organic growth or organic growth can be very slow. Clients like to shop around, which can make it hard to retain existing business. It’s competitive: other law firms can poach valuable partners and bring their clients with them. And whilst entering new markets is an attractive option, it’s expensive, often subject to heavy-regulation and requires the resolve and means to challenge the existing players in that market.

Consolidation can help law firms, which are squeezed between lower-cost entrants and the global players, to compete. This is why we’ve seen many mergers in the mid-market. A combined firm is bigger, less vulnerable to external shocks, and has access to more lawyers and clients. The three-way merger between Olswang, Nabarro and CMS is a good example of this. The year before its merger, Olswang had revenues below £100m and a 77% fall in operating profit. Now, under the name CMS, it’s one of the largest UK law firms by lawyer headcount and revenue.

But mergers aren’t only a defensive move. They can allow law firms to speed-up entry into new markets. For example, were it not for its merger, it would have been difficult for Dentons to open an office in China. Chinese clients, especially state-owned enterprises, are often less likely to pay high legal fees, while local expertise and personal relationships can play a bigger role. There’s also regulation, which prevents non-Chinese lawyers from practicing Chinese mainland law, and plenty of competition from established Chinese law firms. That helps to explain Dentons’ 2015 merger with Dacheng, a firm with decades of experience and an established presence in the Chinese market. Now Dentons is positioned to serve clients investing in China, as well as Chinese clients looking for outbound work at a fraction of the time and cost.

Mergers can also synergies, or at least that’s one of the most frequently used buzzwords to justify an M&A deal. The idea is that when you combine two firms together, the value of the combined firm is more than the sum of its individual parts.

Synergies for a law firm merger could come from cutting costs by closing duplicate offices and laying off support staff. It could also be the fact that a combined law firm could sell more legal services than the two law firms individually, which may be bolstered by the fact that they can cross-sell their expertise to each other’s clients and benefit from economies of scale (e.g. better negotiating paper due to their size).

Finally, mergers can offer reputational benefits. Branding is an essential part of the legal world and combinations gain a lot of legal press. Mergers may allow fairly unknown firms to access new clients and generate far more business if they partner with an established firm. Very large global firms often pride themselves as a ‘one-stop shop’, pitching the fact that their size allows them to service all the needs of a client across any jurisdiction.

But that’s not to say mergers are necessary. Many law firms have grown just fine by organic means. Some attract new clients by developing their sector expertise; for example, Bird & Bird is renown for its intellectual property team and Withers for private client work. Some firms achieve a global reach by opening up their own offices. Others, like Slaughter & May, operate best friend groups, and refer work to a select group of law firms to serve their international clients.

But that’s not to say mergers are necessary. Many law firms have grown just fine by organic means. Some attract new clients by developing their sector expertise; for example, Bird & Bird is renown for its intellectual property team and Withers for private client work. Some firms achieve a global reach by opening up their own offices. Others, like Slaughter & May, operate best friend groups, and refer work to a select group of law firms to serve their international clients.

While it’s true that Swiss vereins have led the likes of DLA Piper and Baker McKenzie to develop very strong brands, collaboration hasn’t always worked out and some law firms have paid the ultimate price. Internal problems and mismanagement plagued the merger of Dewey & LeBoeuf, which, at the time, was called the largest law firm collapse in US history. Bingham McCutchen collapsed for similar reasons. Most recently, King & Wood Mallesons made the mistake of merging with an already troubled SJ Berwin. Poor incentive structures, defections and a fragile merger structure later led to the collapse of KWM Europe. Only time will tell whether Dentons’ 31 plus combinations, as well as the aggressive use of Swiss vereins by other firms, will be a success.

So that’s the why, I’ll now go through the how. Note, in this article, I’ll discuss the mechanics of acquisitions rather than mergers: you can see the difference in the definitions section below. As lawyers, you’ll find acquisitions are more common and you’re more likely to be asked about the acquisition process in law firm interviews and assessment centres.

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

Mergers & Acquisitions Definitions

- Acquisition: The purchase of one company by another company.

- Acquirer/Buyer: The company purchasing the target company.

- Asset purchase: The purchase of particular assets and liabilities in a target company. An alternative to a share purchase.

- Auction sale: The process where a company is put up for auction and multiple buyers bid to buy a target company.

- Due diligence: The process of investigating a business to determine whether it’s worth buying and on what terms it should be bought.

- Debt finance: This means raising finance through borrowing money.

- Equity finance: This means raising finance by issuing shares.

- Mergers: When two companies combine to form a new company.

- Share purchase: When a company buys another company through the purchase of its shares. An alternative to an asset purchase.

- Swiss verein: In the law firm context, this is a structure used by some law firms to ‘merge’ with other law firms. They share marketing and branding, but remain legally and financially separate.

- Target company: The company that is being acquired.

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

Kicking off the Acquisition Process

The buy side

Sometimes the acquirer will have identified a company it wants to buy before it reaches out to advisers. Other times, it’ll work closely with an investment bank or a financial adviser to find a suitable target company.

Before making contact with the target company, the acquirer will typically undertake preliminary research, often with the help of third-party services to compile reports on companies. They’ll look through a range of material including:

- news sources and press releases

- insolvency and litigation databases

- filings at Companies House

- the industry and competitors

The aim is to better understand the target company. The company’s management will want to check for any big risks and form an early view of the viability of an acquisition. Then, if they’re convinced, the first contact may be direct or arranged through a third party, such as an investment bank or consultant.

Note: In practice, lawyers – especially trainees – spend a lot of time using the sources above. Companies House is a useful online resource to find out about private companies. It’s where you’ll find their annual accounts, annual returns (now called a confirmation statement) and information on the company’s incorporation.

The sell side

Sometimes, a target company wants to sell. The founders may want to retire, the company may be performing poorly, or investors may want to cash out and move on.

If a target company wants more options, it may initiate an auction sale. This is a competitive bid process, which tends to drive bid prices up and help the target company sell on the best terms possible. For example, Unilever sold its recent spreads business to KKR using this method.

But, an auction sale isn’t always appropriate. Sometimes the target company will enter discussions with just one company. This may be preferable if the company is struggling, so it can ensure speed and privacy, or the target company may have a particular acquirer in mind. For example, Whole Foods used a consultant to arrange a meeting with Amazon. That was after reading a media report which suggested Amazon was interested in buying the company.

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

Friendly v Hostile Takeovers

In the UK, takeovers are often used to refer to public companies. While we’ll be focusing on acquisitions of private companies, I’ll cover this here because they’re often in the news and sometimes come up in law firm interviews.

The board of directors are the people that oversee a company’s strategy. Directors owe duties to shareholders – the owners of the company – and are appointed by the shareholders to manage a company’s affairs.

If a proposed acquisition is brought to the attention of the board and the board recommends the bid to shareholders, we call this a friendly takeover. But if they don’t, it’s a hostile takeover, and the acquirer will try to buy the company without the cooperation of management. This may mean presenting the offer directly to shareholders and trying to get a majority to agree to sell their shares.

Sometimes, it’s not too difficult; Cadbury’s board first rejected Kraft’s bid and accused the company of attempting to buy Cadbury “on the cheap”. Later, when Kraft revised its offer, the board recommended its bid to shareholders.

In other situations, hostile takeovers can be messy, especially if neither party wants to back down. This was the case in 2011 between the infamous activist investor Carl Icahn and The Clorox Company.

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

Icahn and the Clorox Company

In 2011, Carl Icahn made a bid to buy The Clorox Company (Clorox), the owner of many consumer products including Burt’s Bees. In his letter to the board, Icahn also tried to start a bidding war, inviting other buyers to step in and bid.

Clorox’s board rejected Icahn’s bid and quickly hired Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz, a US law firm, to defend itself. Wachtell wasn’t just any law firm. Icahn and Wachtell had been rivals for decades. In fact, between 2008 and 2011, Wachtell had successfully defended two companies from Icahn.

This was round three.

Clorox adopted a “poison pill” strategy, a tactic that allowed Clorox’s existing shareholders to buy the company’s shares at a discount. This made the attempted takeover more expensive. Martin Lipton, one of the founding partners of Wachtell, had invented the poison pill to prevent hostile takeovers in the 80’s. It was “one of the most anti-shareholder provisions ever devised” according to Icahn. Now, Clorox was using this weapon to stop the activist investor.

But that didn’t stop Icahn. In a scathing letter to the board, he raised his bid for the company. A week later, the board rejected it again.

Icahn made a third bid. This time his letter threatened to remove the entire board. But the board didn’t back down.

Eventually, Icahn did.

The war between Icahn and Wachtell didn’t stop there. In 2013, Wachtell successfully defended Dell from Icahn. A few months after that, Icahn tried to sue Wachtell. In response, the law firm said:

“Icahn takes his bullying campaign to a new level, seeking to intimidate lawyers who help clients resist his demands by making wild allegations and threatening liability. Those tactics will not work here.”

Remember when I said corporate law could be exciting?

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

What are the ways a company can acquire another company?

This is one of the most common questions in law firm commercial interviews.

There are two ways to acquire a company. A company can buy the shares of a target company in a share purchase or buy particular assets (and liabilities) in an asset purchase.

[one_second]

[/one_second]

[one_second]

[/one_second]

Share Purchase

In a share purchase, the acquirer buys a majority of shares in the target company and therefore becomes its new owner. This means all of the company’s assets and liabilities transfer automatically, so, usually, there’s no need to worry about securing consent from third parties or transferring contracts separately. This is great because the business can continue without disruption and the transition is fairly seamless.

However, as the liabilities of a company also transfer in share purchase, it’s important the acquirer investigates the target really well. It’ll also want to try protect itself from known risks when negotiating the acquisition agreement.

For example, suppose three months after the acquisition has completed, a former employee brings an unfair dismissal claim against the acquirer. If this was something they had known about pre-acquisition, they’ll want to be indemnified for those costs (we’ll come back to this later).

Conversely, if they didn’t know about it at the time of the acquisition and they didn’t protect themselves in the acquisition agreement, they’ll have to pay out. That’s one of the risks of doing a share purchase. (Although as we’ll discuss later, there are certain things you can do to reduce the risks of this happening.)

Asset Purchase

Sometimes, an acquirer only wants to buy some of the assets of a company. This was the case with Disney’s recent acquisition of 21st Century Fox, which involved Disney buying the majority of 21st Century Fox’s assets.

Sometimes, an acquirer only wants to buy some of the assets of a company. This was the case with Disney’s recent acquisition of 21st Century Fox, which involved Disney buying the majority of 21st Century Fox’s assets.

We call this an asset purchase. It means that the acquirer identifies the specific assets and liabilities it wants to buy from the target and leaves everything else behind. That’s great because the acquirer will know exactly what it’s getting and there’s little risk of hidden liabilities.

However, asset purchases are less common and can be difficult to execute. Unlike share purchases, assets don’t transfer automatically, so the acquirer may have to renegotiate contracts or seek consent from third parties to proceed with the acquisition.

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

Preliminary Agreements

[one_second]

Confidentiality Agreements

Before negotiations begin, the target company will want the acquirer to sign a confidentiality agreement or a non-disclosure agreement.

This is important because the seller will provide the acquirer with access to private information during the due diligence process. Suppose the acquirer decided not to proceed with the acquisition and there was no confidentiality agreement in place; the acquirer could use this information to poach staff, better compete with the target or reveal damaging information to the public.

So, lawyers for the acquirer and the target company will negotiate the confidentiality agreement. They’ll decide what counts as confidential, what happens to information if the acquisition doesn’t complete, as well as any instances where confidential information can be passed on without breaching the contract.

[/one_second]

[one_second]

Exclusivity Agreements

If an acquirer is dead set on buying a particular target company then, in an ideal situation, it will want to be the only one negotiating with that company. This would give the acquirer time to conduct due diligence and negotiate on price, without pressure from competitors. It also ensures secrecy.

If the acquirer has some bargaining power, it may try to sign an exclusivity agreement with the target company. This would ensure, for a period of time, the target company does not discuss the acquisition with third parties or seek out other offers.

While it’s unclear whether an exclusivity agreement was actually signed, Amazon was clear during early negotiations with Whole Foods that it wasn’t interested in a “multiparty sale process” and warned it would walk if rumours started circulating. That was effective: Whole Foods chose not to entertain the four private equity firms who’d expressed interest in buying the company.

[/one_second]

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

Heads of Terms

The first serious step will be the negotiation of the Heads of Terms (also called the Letter of Intent) between the lawyers, on behalf of the parties. This document details the main commercial and legal terms that have been agreed between the parties, including the structure of the deal, the price, the conditions for signing and the date of completion. It’s not legally binding – so the acquirer won’t have to buy and the target company won’t have to sell if the deal doesn’t go through – but it serves as a record of early negotiations and a guideline for the main acquisition document.

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

Due Diligence

An acquirer can’t determine whether it should buy a target without detailed information about its legal, financial and commercial position. The process of investigating, verifying and reviewing this information is called due diligence.

The due diligence process helps the acquirer to value the target. It’s an attempt at better understanding the target company, quantifying synergies and determining whether an acquisition makes financial sense.

Due diligence also reveals the risks of an acquisition. The acquirer can examine potential liabilities, from customer complaints to litigation claims or scandals. This is important because underlying the process of due diligence is the principle of caveat emptor, which means “let the buyer beware”. This legal principle means it’s up to the buyer to fully investigate the company before entering into an agreement. In other words, if the buyer failed to discover something during due diligence, it’s their problem. There’s no remedy after the acquisition agreement is signed.

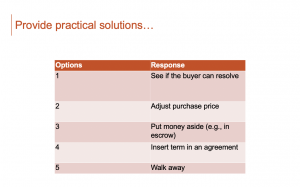

So if the problems uncovered during the due diligence process are substantial, the acquirer may decide to walk away. Alternatively, it could use this information to negotiate down the price or include terms to protect itself in the main acquisition document.

In an asset purchase, due diligence is also an opportunity to identify all the consents and approvals the buyer needs to acquire the company.

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

Due Diligence Teams

The acquirer will assemble a team of advisers, including bankers, accountants and lawyers, to manage the due diligence process. The form and scope of the review will depend on the nature of the acquisition. For example, an experienced private equity firm is likely to need less guidance than a start-up’s first acquisition. Likewise, a full due diligence process may not be appropriate for a struggling company that needs to be sold quickly.

Due diligence isn’t cheap, but missing information can be devastating. In a Merger Market survey, 88% of respondents said insufficient due diligence was the most common reason M&A deals failed. HP had to write off $8.8 billion after its acquisition of Autonomy – which was criticised for being a result of HP’s ‘faulty due diligence‘. Few also looked into organisational compatibility in the merger between AOL and Time Warner, which led to the “biggest mistake in corporate history”, according to Jeff Bewkes, chief executive of Time Warner. In 2000, Time Warner had a market value of $160 billion. In 2009, it was worth $36 billion.

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

Types of Due Diligence

[one_second]

Financial due diligence

This involves assessing the target company’s finances to determine its health and future performance.

[/one_second]

[one_second]

Business due diligence

This involves evaluating strategic and commercial issues, including the market, competitors, customers and the target company’s strategy.

[/one_second]

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

Legal Due Diligence

Legal due diligence is the process of assessing the legal risks of an acquisition. By understanding the legal risks of an acquisition, the acquirer can determine whether to proceed and on what terms.

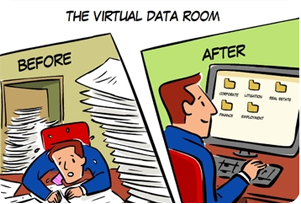

The acquirer’s lawyers have a few ways of obtaining information for their due diligence report. They’ll prepare a questionnaire for the seller to complete and request a variety of documents. This will all be stored in a virtual ‘data room’ for all parties to access. They may also undertake company, insolvency, intellectual property and property searches, interview management and, if appropriate, undertake on-site visits.

The Report

It’s important that departments and advisers coordinate to prevent overlap and save costs when compiling the due diligence report.

It’s important that departments and advisers coordinate to prevent overlap and save costs when compiling the due diligence report.

Law firms tend to have a system to manage the flow of information and trainees are often very involved. They’ll review, under supervision, much of the documentation and flag up potential risks.

Legal due diligence reports are typically on an ‘exceptions’ basis. This means they’ll flag to the client only the material issues. You can see why this is valuable to the client; rather than raising every possible issue, they’ll apply their commercial judgement to inform the clients about the most important issues.

The report will propose recommendations on how to handle each identified issue. This may include: reducing the price, including a term in the agreement or seeking requests for more information. If the issue is significant, lawyers will want to tell their client immediately, especially if what they find is very serious.

Note, due diligence is a popular topic for interviews. You may be asked to recommend possible solutions to issues uncovered during the due diligence process or asked to discuss the issues that different departments may consider (see examples below).

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

What are lawyers looking for during due diligence?

[one_second]

What might Corporate investigate?

The group structure of the target, including the operations of any parent companies or subsidiaries

The company’s constitution, board resolutions, director appointments and resignations, and shareholder agreements.

Important details from Insolvency and Companies House searches

Copies of contracts for suppliers, distributors, licences, agencies and customers.

Termination or notification provisions in contracts

What do they want to know?

Whether shareholders can transfer their shares (share purchase)

Whether shareholders need to approve the sale and the various voting powers of shareholders

Any change of control provisions in contracts

Whether the target can transfer assets (asset purchase)

Any outstanding director loans, director disqualifications, or conflicts of interest

[/one_second]

[one_second]

What might Finance investigate?

Existing borrowing arrangements including loan documents and any guarantees

Correspondence with lenders and creditors

Share capital, allocation and employee share schemes

Assets and financial accounts

The company’s ability to pay current and future debts

Any prior loan defaults, credit issues or court judgements

What do they want to know?

Details of ownership and title to the assets

Any liabilities which could limit the performance of the target

Whether borrowing would breach existing loan terms

Whether the loan agreements have any change of control clauses

Whether security has been granted over the target’s assets to lenders

[/one_second]

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

[one_second]

What might Litigation investigate?

Details of any past, current or pending litigation

Disputes between the company, employees or directors

Regulatory and compliance certificates

Any judgements made against the company

Insurance policies

What do they want to know?

The risk of outstanding or future claims against the company

Details of any regulatory or compliance investigations

Potential issues or threatened litigation from customers, employees or suppliers in the past five years

[/one_second]

[one_second]

What might Property investigate?

Documents relating to freehold and leasehold interests

Inspections, site visits, surveyors and search reports

Health and safety certificates and building regulation compliance

Leases and licences granted to third parties

What do they want to know?

Whether the property will be used or sold

Property liabilities

Title ownership and lease/licensing terms

The value of the properties

Details of regulatory compliance

[/one_second]

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

[one_second]

What might Employment investigate?

Director and employee details, and service contracts

Pension schemes and employee share schemes

Pay, benefits and HR policy information

Information in relation to redundancies, dismissals or litigation

What do they want to know?

Plans to retain key managers, redundancy and compensation

Pension scheme deficits

Termination or change of control provisions

Compliance with employment law and consultation

Risks of dismissal claims

Evaluate post-acquisition integration

[/one_second]

[one_second]

What might Intellectual Property investigate?

List of any trademarks, copyright, patents, domain names and any other registered intellectual property

Registration documents and licencing agreements

Litigation and related correspondence

Searches at the Intellectual Property Office

What do they want to know?

Current or potential disputes, claims of threatened litigation in relation to infringement

Whether the seller has renewed trademarks

Who has ownership of the intellectual property

Whether they can transfer licenses and gain consents

Details of critical assets, confidentiality provisions and trade secrets

[/one_second]

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

The Acquisition Agreement

The main legal document is the sale and purchase agreement or “SPA”. It sets out what the acquirer is buying, the purchase price and the key terms of the transaction.

Purchase Price

A company will usually pay for an acquisition in cash, shares, or a combination of the two.

Cash is a good option if an acquirer is confident in the acquisition. If it believes the shares are going to increase in value (thanks to synergies), paying in cash means it can soak up the benefits without having to give up ownership of the company. It is, however, expensive to pay in cash. The buyer must raise money if it doesn’t already have enough cash reserves by issuing shares or borrowing. Most sellers also want cash. It means they’ll know exactly how much they’re getting and don’t have to worry about the future performance of a company.

Other times, an acquirer will want to use shares to pay for an acquisition. The target’s shareholders will get a stake in the acquirer in return for selling their shares. If the value of the acquirer’s shares increases, the shareholders may get a better return. Often, this option will be more attractive for an acquirer as it doesn’t use up cash. Receiving shares can also be valuable for the seller if they’re gaining shares in a promising company. Conversely, however, they must bear the risk that the value of the acquirer falls.

Key terms of the transaction

Both parties will make assurances to each other in the form of terms in the SPA. These terms are heavily negotiated between lawyers.

Warranties and representations

Warranties are statements of fact about the state of the target company or particular assets or liabilities. For example, the seller may warrant that the target isn’t involved in any litigation, that its accounts are up to date and that there are no issues with its properties. If these warranties turn out to be false, the acquirer may claim for damages. However, there are limitations: the acquirer will have to show that the breach reduced the value of the business and that can be hard to prove.

During negotiations, the seller will try to limit the scope of the warranties. It’ll also prepare a disclosure letter to qualify each warranty. For example, the seller may qualify the above warranty with a list of outstanding litigation claims. If the seller discloses against a warranty, they won’t be liable for a breach. Disclosure is also useful for the acquirer because it may reveal information that was not found during due diligence.

The acquirer will want some of these statements to be representations. Representations are statements which induce the acquirer to enter into a contract. If these are false, the acquirer could have a claim for misrepresentation. That could give the acquirer a stronger remedy, including termination of the contract or a bigger claim for damages. This is why the seller will usually resist giving representations.

Indemnities

Indemnities are promises to compensate a party for identified costs or losses. This is appropriate because the acquirer may identify potential risks during due diligence; for example, the risk of an unfair dismissal claim or a litigation suit. The acquirer can seek indemnities to be compensated for these particular liabilities arising in the future. This is a way to allocate risks to the seller: if the event occurs the acquirer will be reimbursed by the seller.

Conditions Precedent

The SPA may be signed subject to the satisfaction of the conditions precedent or “CPs”. These are conditions that must be fulfilled before the acquisition can complete. That could mean, for example, securing consent from third parties, shareholder approval or merger clearance. Trainees are often responsible for keeping track of the conditions precedent checklist, and they’ll need to chase parties for the approvals to ensure all conditions are satisfied.[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

Signing and Completion

Signing and Completion

This is the big day. Signing can take place in person or virtually. Each party will return the SPA with their signature in accordance with the relevant guidelines. It’ll be the trainees responsibility to check that the SPA has been signed correctly and to collate the documents.

Final Thoughts

If you’re reading this to prepare for an interview, I’d suggest you explore the “acquisition structure”, “legal due diligence” and “warranties and indemnities” sections – these are common case-study questions. We cover this in more detail and with practice interview answers in our mergers and acquisitions course, which is free for TCLA Premium members.

[divider height=”30″ style=”default” line=”default” themecolor=”1″]

[blog_teaser title=”” title_tag=”h3″ category=”” category_multi=”” margin=”1″]