The Big 4’s (KPMG, Ernst & Young, Deloitte and PwC) traditional accounting services have become increasingly commoditised and less profitable. They\’ve experienced slower growth and face greater legal risks. In order to respond to this market shift the Big 4 have been fighting a constant battle over the last 30 years to become major players in the legal industry to diversify their business.

Throughout the 1990’s the Big 5 (as it was known back then) rapidly expanded its legal arms to the scale of the largest international law firms at the time. However, they suffered a heavy defeat following the ‘Enron scandal’ and subsequent collapse of accounting firm Arthur Anderson in 2001.

In the aftermath of this there was a surge of intense regulation and many assumed their legal ambitions were dead in the water, as the lid had been blown on the potential for conflict of interest systemically arising from a business with huge legal and auditory divisions. However, it seems this was only the first clash in what will prove to be an on-going campaign to revolutionise the legal industry.

The Rise of The Big 4

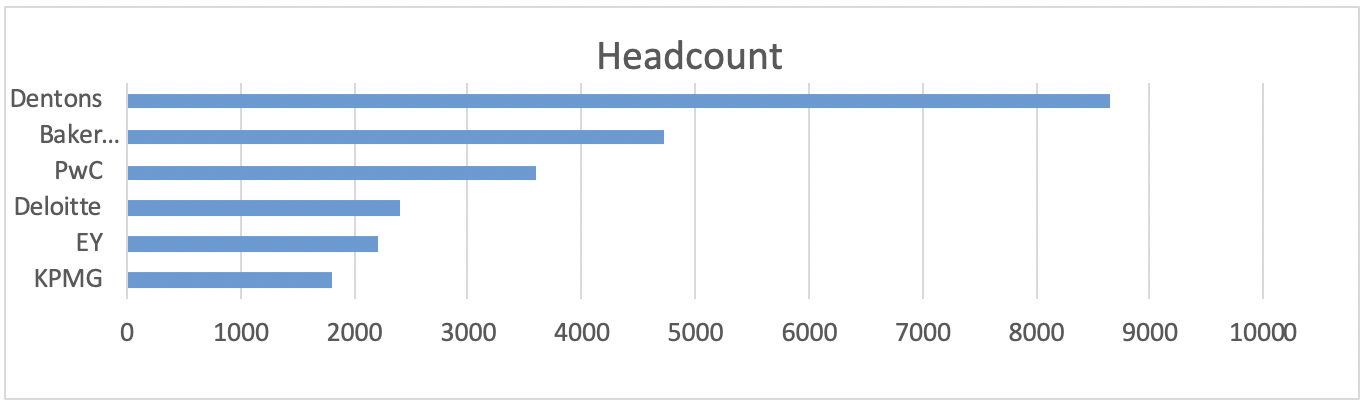

A surge of liberalisation across the legal industry has enabled the Big 4 to start rapidly rebuilding their legal arms (see table below for a comparison to the largest global law firms as of 2018) and set their sights on seizing a substantial share of the lucrative £700bn global legal services market. This is most evident in the UK following the introduction of the Legal Services Act in 2007, which allowed licenced bodies to launch an ‘alternative business structure’ to offer legal services. PwC was the first of the Big 4 to take advantage of this in 2014 with the launch of PwC legal, but since then all of the Big 4 have their own legal services offering (Deloitte being the last to join in 2018).

Headcount of the Big 4 and the largest global law firms in 2018

The Current Threat – Key Stats

The Big 4 are poised to exploit one of the biggest problems currently facing the legal industry, what Richard Susskind describes as the “more-for-less problem”. This is where many of law firms’ largest clients are demanding a better service at a lower rate (up to 50% less) due to budget constraints. However, traditional law firms have struggled to shift their pricing models from the classic hourly rate (often any ‘shift’ in pricing model is in fact simply a re-packaging of fixed/hourly rates that results in no real cost saving) or innovate to the extent that this is commercially viable. The Big 4 on the other hand do not have the same rigidity when it comes to pricing and are far better position in the technological arms race to increase efficiency. The Big 4 have three main weapons in their arsenal that pose a threat to international law firms and can be used to overcome the more-for-less problem:

1. Established Relationships with most law firms existing clients

The Big 4 regularly works with FTSE 100 companies and to that extent most of international law firm’s largest and most influential clients. This existing relationship will make it far easier for the Big 4 to leverage their legal services to gain work, especially if they can offer a solution to the more-for-less problem, whilst law firms prove incapable of making substantial change.

2. Capital Reserves

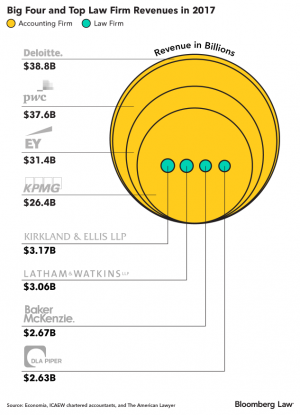

One of the most formidable weapons in the Big 4’s arsenal is their huge revenues. For context on just how disproportionate this is, KPMG’s revenue in 2019 was $29bn, compared to the world’s largest international law firm by revenue Kirkland & Ellis at a relatively minor $3.7bn (see Bloomberg Law infographic below for a visual representation from 2017).

This means that the Big 4 have far more capital at their disposal than traditional law firms to invest in game-changing legal tech and become market leaders in the technological arms race. This puts the Big 4 in a far better position to address the “more-for-less” problem than traditional law firms, as technology is at the core of increasing efficiency to enable the low-cost legal billing. For instance, the use of AI can automate commoditised legal work and remove the need for trainees to bill for more administrative-based work (for instance see ‘Smarter Drafter’ – an AI capable of drafting documents in a matter of minutes or Kira Systems which can automatically identify and extract key provisions from a contract, required for due diligence). One only needs to take a look at some of the recent headlines to see that the Big 4 mean business when it comes to legal tech:

This means that the Big 4 have far more capital at their disposal than traditional law firms to invest in game-changing legal tech and become market leaders in the technological arms race. This puts the Big 4 in a far better position to address the “more-for-less” problem than traditional law firms, as technology is at the core of increasing efficiency to enable the low-cost legal billing. For instance, the use of AI can automate commoditised legal work and remove the need for trainees to bill for more administrative-based work (see ‘Smarter Drafter’ – an AI capable of drafting documents in a matter of minutes or Kira Systems which can automatically identify and extract key provisions from a contract, required for due diligence).

One only needs to take a look at some of the recent headlines to see that the Big 4 mean business when it comes to legal tech:

3. The One Stop Shop Model

The Big 4 are by no means simply trying emulate leading law firms by offering a shinier and cheaper service, but instead are responding to changing market demands and offering ‘fully integrated solutions’ or a ‘one-stop shop’ model. As Jürg Birri, KPMG’s Global Head of Legal Services, said, “Our approach is different. We’re not a traditional law firm, and we’re not copying the approach of a traditional law firm. We focus on offering our clients integrated legal advice and technology-led solutions and methodologies, in combination with a range of alternative legal managed services.” In other words, the Big 4 can offer to single-handedly complete an entire transaction for their clients through the uses of deep industry experience, a global network and integrated businesses. For instance, PwC recently completed the entirety of tasks associated with the sale of Darrell Lea and were duly awarded Mid-Market M&A Financial Adviser of the Year in Australia. The streamlined integrated service not only allows for cost savings, but is also desirable from a project/matter management perspective, as it is much easier for a client to be guided by a single trusted advisor from start to finish.

Regulatory Challenges in the UK

However, the Big 4’s legal ambitions in the UK may soon be thwarted following the Competition and Markets Authority\’s (CMA) recommendation of an ‘operational split’ between the Big 4’s accounting practice and their other non-audit professional services (including the increasingly growing legal services). The recommendations are intended to address what the CMA described as ‘serious competition problems in the UK audit industry’. The purpose behind this recommendations to increase competition in the audit market, by removing the Big 4’s ability to share profits with their other professional services businesses (which enables the benefits of economies of scale – creating barriers to entry for smaller businesses) and to prevent business decisions being influenced by their other professional services. While this has not yet been put into law, this could seriously curtail the Big 4’s legal ambitions in 12-18 months as the newly split business would no longer be able to benefit from their audit counterpart’s large war chest. However, it is questionable how much this recommendation would prevent the rise of the Big 4 (if it’s even ever implemented), as they will still be able to offer clients a one-stop shop. Plus, in the long term, it is highly likely that the market will follow the general trend of deregulation and the floodgates will be opened once again (one only needs to look at the rise and fall of the Big 4 in the US legal market).

Equally, it must be remembered that the Big 4’s legal ambitions are on a global scale and, while they may be facing regulatory challenges in the UK, the opposite is occurring across the pond. Several western US states are pushing to relax State Bar Rules to provide more access to justice, and, in doing so, they are inadvertently opening the floodgates to the Big 4 which have previously been held back by the Sarbanes-Oxley-Act (which currently prohibits audit firms from providing certain non-audit services to clients). Moreover, Alternative Business Structures have been legal in Australia for years and many other countries across the globe are actively heading towards liberalization, such as Canada, South Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong.

Concluding Thoughts – Is the threat of the rise of the Big 4 a ’Trojan Horse’ or is it overstated?

The big question is: should traditional law firms be worried or is the threat overstated? There are two main misconceptions surrounding the Big 4 leading to a sense of complacency across some of the legal industry:

Limited Practice Area Capabilies

Many firms are under the impression that their specialist practices need not worry as much of the Big 4’s current focus is on developing their existing strengths in areas such as Immigration, Tax and Cyber-Security. Indeed, PwC created a strategic alliance with Fragomen in 2017, an international immigration law firm and Deloitte undertook a similar arrangement with U.S immigration law firm Berry Appleman & Leidan. However, law firms need to look beyond the headlines, as the Big 4 may be focused on consolidating their strengths at the moment, but in the long term their sights are set higher. Indeed, they have already been on a hiring rampage acquiring both litigators and transactional lawyers as part of their long term strategy – highlighted by Deloitte who recently hired senior Magic Circle M&A partner Michael Castle

Mid-Market Focus

Equally, there is a belief that clients value the expertise and reputation of the top law firms so highly, that only mid-market work is in contention. But it is questionable whether reputation and expertise alone will be enough to retain clients for high end work in the long term. As the Big 4 are becoming increasingly attractive alternative providers – laterally hiring top talent and making greater strives to effectively address the “more-for-less” problem. Denton’s CEO Elliot Portnoy warns against this complacency, describing what he calls “the myth of legal exceptionalism” – the belief that the work of top law firms is so specialised that an accounting firm could never compete at that level. Ultimately, although the Big 4 may not be competing for high-end work right now, top law firms should still be warry as Fieldfisher managing partner Michael Chissick warns: “They’re not going after the top 20 law firms, because they audit many of them and have close referral relationships, so they’re going after the mid-tier strata of work with the view to – once they’ve conquered and dominated that space – going after the space dominated by the big firms.

Ultimately the threat is real and regulation will likely only serve as a temporary hurdle. In the long term, the Big 4 will be moving beyond Tax, Immigration and Cyber-Security and the mid-market into a completely integrated and full service offering capable of competing with the leading firm’s in their respective fields. Even now the Big 4 are already winning work from law firms – a 2017 Thomson Reuters report highlighted that 23% of laws firms surveyed had already competed and lost work to the Big 4 within the last year. While there will always be some demand for specialised legal services, in order for law firms to survive and successfully compete with the accountants they must adapt – either through increased collaboration (e.g. Allen & Overy\’s collaboration with Deloitte to create Margin Matrix) or through innovation and alternative billing structures.